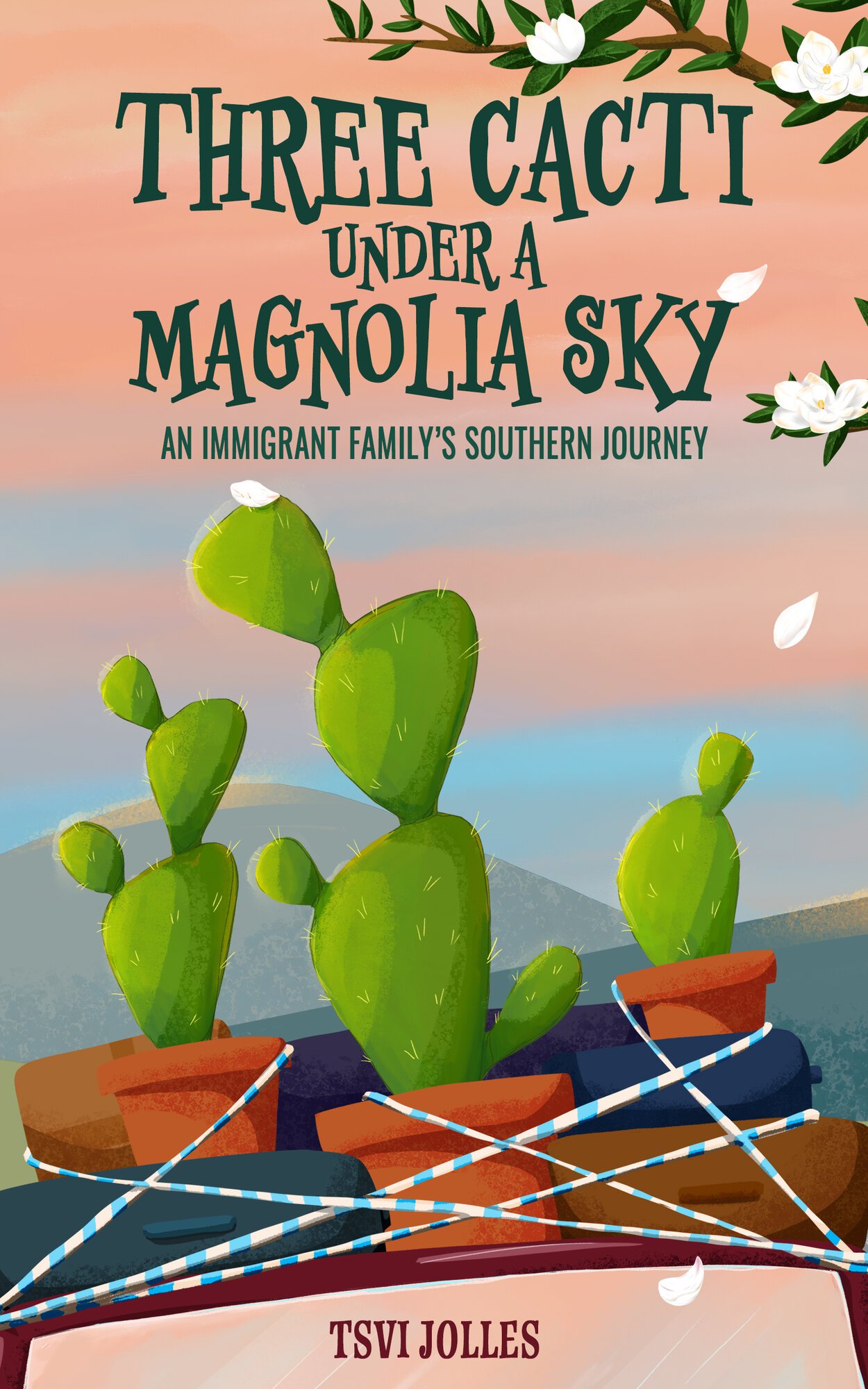

Immigration isn’t always dramatic. Sometimes it looks like doing exactly what you were asked — and still getting it wrong.

This is the first chapter of Three Cacti Under a Magnolia Sky: “How We Ruined Valentine’s Day for America.”

***

This story begins with an ordinary email from our son’s kindergarten teacher, sent about a month and a half after we relocated for my wife’s job to Johns Creek, a northern suburb of Atlanta. It ends—perhaps predictably—with a shaming tweet from the president himself. Not the PTA president, but the president of the United States.

That email, sent through the class mailing list, asked us to get ready for Valentine’s Day—the day of Saint Valentinus of Terni, Guardian of Glitter, Hearts, and Last-Minute Crafting. More specifically, we were asked to help our six-year-old, TJ, create greeting cards that showed “effort, creativity, and personal expression,” as Mrs. Rogers kindly put it.

She also included a link to $4.99 packs of twenty-five ready-made Valentine cards at Walmart, followed by directions to the store and the exact aisle and endcap, in case some parents—newcomers like us, perhaps—needed a translation of what “effort, creativity, and personal expression” really meant here.

According to Mrs. Rogers, TJ’s kindergarten teacher, each child was to bring twenty-five cards to exchange with classmates, and go home with twenty-five in return.

Fast forward to two nights before Valentine’s Day, when our modest two-bedroom rented condo in the Rivermont neighborhood no longer resembled a home at all. By nightfall, our rented dining table from Aaron’s had transformed into a small Valentine factory, commanded by a single, determined artisan—my wife.

She spread her materials across the table with the seriousness of someone who had cleared her schedule and did not plan to stop halfway: stacks of white and pink paper, scissors and glue sticks lined up like materials at the ready, and a scattering of tiny paper hearts laid out like evidence from a joyful crime.

A playlist of soft eighties pop—George Michael, Cyndi Lauper, a few power ballads that refuse to die—floated from her phone, giving the room exactly the kind of sentimental soundtrack Valentine’s Day seems to require. Every so often, she hummed along or tapped her foot, fully immersed in her craft.

I watched her from the side, sitting on the sofa—also from Aaron’s, like nearly all our furniture during those first weeks in the States—as she disappeared into the quiet joy of making things. It was so disarming and peaceful that I almost wanted to join her, but I knew better. She was one of those solo artists, not to be approached mid-process. Still, after a while, I couldn’t help myself and drifted closer, leaning over the table.

“I mean, this is real art,” I said carefully, “but isn’t the whole idea that the kids do something themselves? You know… glue a thing. Draw a heart. Misspell a word.”

She looked at me the way you do when someone speaks out of turn at a meeting they were invited to observe, not join.

“What happened to you?” she asked.

“To me?”

“Yes. Did you swallow some of that glue by accident?” she said. “This is TJ. You look like you just landed from space and don’t know the kid.”

“You’re right,” I said, making a quick mental note. “I’m sorry. I forgot. He’s my son. The one who will never touch anything sticky unless it’s an iPad screen.”

I paused, then added. “Still, you could have just gone to that aisle in Walmart, met all the other parents there, chatted a bit. It’s good to meet people. We’re new.”

She smiled without looking up, already reaching for the next sheet of paper. “Well, how many Walmarts are there in the States? You probably know. You collect that kind of information in your head.”

“I don’t know,” I said. “Three thousand? Four?”

“Alright,” she said. “And every one of them has the same aisle, with the same Valentine cards, the same pink plastic, and the same parents trying to look thoughtful in under three minutes. Which means every ‘special’ card you buy was also bought by three thousand other special parents. That’s not something I can live with.”

She handed me one of the finished cards.

“But this,” she said, her voice softening, “there’s only one greeting card like this in the world.”

I stood there, card in hand, feeling the softness of the paper, the slight roughness of the hand-cut edge, the tiny heart placed just off center—unmistakably my wife’s touch.

“It’s beautiful,” I said. “I just want to point out that you started when there was still daylight outside, and now it’s—what is it—two hours past TJ’s bedtime. And you have a workday tomorrow. As a designer. You might need some rest from this kind of work.”

“That’s the only way I know,” she said, lining up the next piece. “I can’t send you to Walmart and then send TJ in with pre-made cards. That’s just not me. I’m me, the way you’re you—you’re never going to stop writing books. Same obsession. Different aisle.”

She paused, then added, “What keeps me going, instead of curling up with a book, is knowing they won’t forget TJ’s cards. Not after Valentine’s Day. He’ll be the kid with the handmade ones.”

She said it so calmly, so confidently, that I should have paid closer attention.

Thirty-six hours passed. Plenty of time for all the glue to dry.

Morning.

We wake up.

“Happy Valentine’s Day,” my wife says.

“Yeah… why not,” I answer. I’m not really used to this holiday or its greetings. It’s my first Valentine’s Day in the States, and if it weren’t for Mrs. Rogers’s email, the mountain of heart-shaped cookies stacked by the checkout at Publix I’d seen the night before, and my wife standing there with a trace of pink paper stuck to her sleeve and the look of someone who hadn’t slept much, I would have thought it was just another ordinary morning—one of those non-glittery, slow-developing ones.

We sit down for breakfast. Scrambled eggs, tahini, bell peppers, cucumbers, tomatoes, sourdough and rye, oatmeal, coffee for her, tea for me, orange juice for TJ.

We finish eating. I notice my wife has only eaten half her plate, which is unusual.

“So,” she asks TJ, “are you as excited as I am?”

He murmurs something in response.

She hands him his Valentine’s box, also handmade—a shoebox wrapped in pink paper and filled with cards. He holds it with both hands, excitement spilling over from his mom, and it feels like a good moment, one of those small family rituals kids remember.

I should feel blessed at this point.

He misses the yellow school bus because we take our time, but we don’t read it as any kind of sign from the universe. Instead, my wife cheerfully offers to drive him to school and says she’ll head straight to work afterward.

“So once again—happy Valentine’s Day, sweetheart.”

“Yeah,” I say.

A few hours pass. Maybe two, maybe three. I’m back at our condo after some grocery shopping—nothing dramatic. Just a regular writing day.

Yes—this is a story that mostly takes place in one location, at least from my point of view.

On TV, they say something very upsetting has happened in Johns Creek, north of Atlanta, and they’ll update us shortly.

Breaking News.

Usually, I don’t stick around for breaking news, especially not the very local kind. But this time I’m curious. What could possibly happen here on Valentine’s Day? After all, everything is supposed to be full of love.

“Well, here’s what we know,” the anchor begins. He looks about thirty, African American, sharp-eyed, with the kind of standard, dimpled smile you see on local news billboards. “An Israeli family in a northern suburb of Atlanta sent their six-year-old to kindergarten this morning with only greeting cards in his Valentine’s box. Jessica, I understand you have more details?”

“Yes, good morning, Steven,” Jessica said. “I’m standing in the courtyard at the entrance of Barnwell Elementary here in Johns Creek, an area often referred to as Alpharetta. This is a community known for its peaceful suburban life, but this morning something unexpected happened. An Israeli family—again, I emphasize Israeli—decided that Valentine’s Day is strictly for greeting cards, without any sweets or small gifts attached. So this brave Israeli couple—I emphasize brave—sent their child to school with nothing but paper cards, featuring writing in both English and Hebrew.”

“Are we absolutely sure there were no sweets?” Steven asked. “Maybe hidden at the bottom of a double-layer box, Jessica? I mean, we’re talking about normal people here.”

“From what teachers told us, Steven, there wasn’t a single piece of candy. I assume they double-checked the box before sharing this information.”

“Just cards—like the ones from Kroger? Or Amazon?”

“Get this, Steven. Not store-bought cards at all. These were handmade—crafted at home, with a personal touch. Wild, right? That’s the official information so far. Behind me, you can see large teams of police officers, backed by representatives from American M&M’s, Hershey’s, KitKat, and more. I should note there was quite a commotion here earlier, until local police arrived and restored order.”

“What’s the current focus on the ground, Jessica?”

“Right now, Steven, most professionals are trying to make their way into Mrs. Rogers’s kindergarten classroom—the one affected by this Valentine’s Day… delivery of greeting cards without sweets.”

“You mean psychologists, for example?”

“Yes, Steven, among others. There’s no question this is a culture shock for the children, and the teams are trying to prevent any long-term emotional consequences.”

“Jessica, thank you for your reporting.”

I don’t know if there was more to the story or how long it continued, because at that moment I yanked the television cord out of the wall—socket and all.

With a trembling hand, I reached for the table beside me. I remembered I’d left my phone there earlier.

I called her—my wife. The one who chose to give up sleep to make Valentine’s Day cards from scratch instead of just grabbing a ready-made pack from aisle thirty-eight or so and throwing in a few Hershey’s Kisses and some Nerds.

“Don’t ask what happened,” I said as soon as she picked up.

“I know. My whole office is watching it now. All the TVs are on. The important thing is—they haven’t mentioned our name yet, right?”

“No,” I said. “That’s our one bit of luck.”

We reassured each other that it was all a small mistake—a misunderstanding, a lack of familiarity with the local culture. By next Valentine’s Day, we said, everyone would forget about it, and we’d make up for it with a ready-made box of sweets and those grab-and-go Valentine cards from Kroger or Target.

Finally, a change of scenery.

It’s boring to stay home all day, especially on Valentine’s Day.

I went out and stood where the neighborhood parents usually stand, waiting for the yellow bus to bring their kids home. This time, though, I noticed something was different. The parents were avoiding eye contact. Something felt off. Had the news mentioned the Rivermont neighborhood? We’re more or less the only Israeli family here.

I managed to pull one of the mothers aside and asked if she’d heard about that family—the Israeli one, I emphasized—who sent their kid to school with only cards and no sweets.

“I heard,” she said, already turning back toward the group, all of them standing with their backs to me.

“Well, maybe another Israeli family just moved into the neighborhood…” I said, stopping her with a small gesture.

“With the same name as yours?” she snapped, barely looking at me.

I searched for words, but before I could find any, she pulled out her phone and held it up. Still Twitter back then—pre-X. I recognized the layout instantly, and then the face of Donald Trump filled the screen.

“Thank you very much, Jolles family,” the tweet read. “You’ve made me consider moving the embassy back to Tel Aviv.”

“It reached the president?” I asked.

She nodded once and slipped back into the cluster of parents without another word.

The bus arrived.

Deep breath.

TG got off first. He always gets off first.

In his hand, he held a decorated box—the same one his mother had made and filled with twenty-five greeting cards, exactly as Mrs. Rogers requested.

“Hey, Dad, I had a great day at school,” he said. “Guess what I have in the box?”

He didn’t wait for an answer—good thing, because I didn’t have one. He opened the lid right there. Inside were chocolates, heart-shaped candies, small toys, and even a few tiny, surprisingly respectable greeting cards.

“You didn’t tell me Valentine’s Day was so much fun,” he said. “It totally surprised me.”

“Yes,” I said. “That’s exactly what we were going for. A surprise effect.”

We walked home together. For some reason, the parents around us chose a different route.

As we passed the neighborhood mailboxes, I stopped and wondered whether I should open ours now and pull out the letter officially announcing that our family had become persona non grata in the United States—or wait until after Valentine’s Day.

I decided to wait a few more hours.

Might as well enjoy the holiday atmosphere.

Happy Valentine’s Day.

Interested in reading the whole book?

Join the advance reader list to receive a free eBook copy in exchange for an honest review.

Reviews are entirely optional, but much appreciated.

After clicking, please check your email to confirm your signup for this early reader list.